The number eight is believed to be lucky in some Asian countries, so a bank account numbered 88888 in Singapore should be luckier than most. Instead, it is now associated with one of the financial world’s most infamousberüchtigtinfamous crimes. The man responsible for the 88888 account was Nick Leeson, the original “rogueverbrecherischrogue trader”.

Back in 1985, Leeson was an 18-year-old school-leaver about to join Coutts & Company, bankers to the Queen, in London. The son of a plastererStuckateur(in)plasterer, he was hard-working, financially astutescharfsinnig, cleverastute and highly ambitious. At the age of 20, Leeson to transfer towechseln antransferred to the Futures and Options division of investment bank Morgan Stanley. Determined to become a trader, he to engineerarrangieren, in die Wege leitenengineered a move to Barings Bank in July 1989 and made a name for himself by saving the Jakarta overseas operation almost £100 million in liabilitiesSchulden, Verbindlichkeitenliabilities. In 1992, he was appointed general manager of Barings Futures Singapore (BFS), a new operation in futures markets on the Singapore Monetary Index (SIMEX).

Initially, the move appeared to be a success, with Leeson earning big money for himself and for Barings by successfully betting on the future direction of the Nikkei Index and to exploitausschöpfenexploiting the small margin between prices on the Tokyo and Singapore exchanges. That he was also to bend the rulesdie Vorschriften umgehenbending the rules and making unauthorized transactions was something nobody seemed to notice or care.

“The recovery in profitability has been amazing, ... leaving Barings to conclude that it was not actually terribly difficult to make money in the securitiesWertpapier-securities business,” wrote Peter Baring, chairman of that company, in a letter to the Bank of England in 1993.

Leeson has always claimed that he set up the 88888 “error account” to help hide losses to incur sth.etw. erleiden, sich etw. einhandelnincurred by a junior colleague. However, most reports, including the official Singapore government commission investigation into the Barings disaster, say that Leeson opened “88888” as a trading account in 1992 and subsequentlyspäter, im Anschlusssubsequently used it to hide losses, to book fictitious trading operations and to create artificial profits. The Singapore report states that transactions conducted in account 88888 “consistently reflected losses from the time the account was opened”.

The sums involved were huge, but they were as remote for Leeson as they were for most of the other traders. “We just had to buy and sell abstract numbers for a living,” Leeson writes in his autobiography, Rogue Trader. “They were big, but they were unreal, and they changed price with astonishingerstaunlichastonishing speed.”

Leeson describes a macho world of big money, big egos, greedHabgiergreed and recklessunbekümmert, leichtsinnigreckless hedonismGenusssuchthedonism, drinking to excess, partying, attending extravagant functions, spending huge sums on property, luxuries and travel. Unable to admit his mistakes, knowing he would lose everything, Leeson reacted as every bad gambler would — by chasing his losses. He gambled that the Nikkei would rise, buying up large quantities of contracts to try to influence the market upwards. Instead, it fell, notablyinsbesonderenotably in the aftermathnachin the aftermath of the Great Hanshin (Kobe) Earthquake of 17 January 1995. Even before the tremorBebentremors had to subsidenachlassen, sich legensubsided, it was clear that Leeson’s deals to spell disasterUnglück bedeutenspelt disaster.

Did his supervisors and the Barings’ executives and auditorBuchprüfer(in)auditors really to suspectahnensuspect nothing, however? How could the regional manager of Barings South Asia to dismissabtundismiss a multimillion dollar accounting anomaly as “a back office glitchFunktionsstörung, Panneglitch”? According to Leeson, and backed by official reports, Barings’ officials saw what they wanted to see at BFS — success and profits — and they did not see what they did not wish to see — fraudBetrugfraud, mismanagement, incompetence and a huge hole in their balance sheetBilanzbalance sheet.

It is interesting today to read a copyExemplarcopy of “Pulling fraud out of the shadows”, the 2018 Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey created by accountancy giants PricewaterhouseCoopers. It shows that 49 per cent of global organizations admit they experienced economic crime in the previous two years, with 52 per cent of the frauds being carried out by people inside the organizations. Furthermore, the report suggests that many of the organizations that did not report any fraud might well be ignoring or overlooking it.

49 per cent

of global organizations admit they experienced economic crime in the previous two years.

How does it happen? How does a rogue trader escape detection? “The way most white-collar crimeWirtschaftsverbrechenwhite-collar crime works is by manipulating institutional psychology. That means creating something that looks as much as possible like a normal set of transactions,” explains Dan Davies, author and former Bank of England economist, writing in The Guardian.

To the Barings boardVorstandboard, Leeson was a wunderkind, a one-man money machine set to exploit market mechanisms that to yieldabwerfenyield big profits. Despite his increasingly large and frequent requests for funding from London (to meet his increasingly heavy losses), none of the senior executives properly checked or challenged him. “As each day went on, and my requests continued to be met, the explanation to dawndämmerndawned on me,” writes Leeson in Rogue Trader. “They wanted to believe that it was all true... I must be doing more business, therefore we would all be richer.”

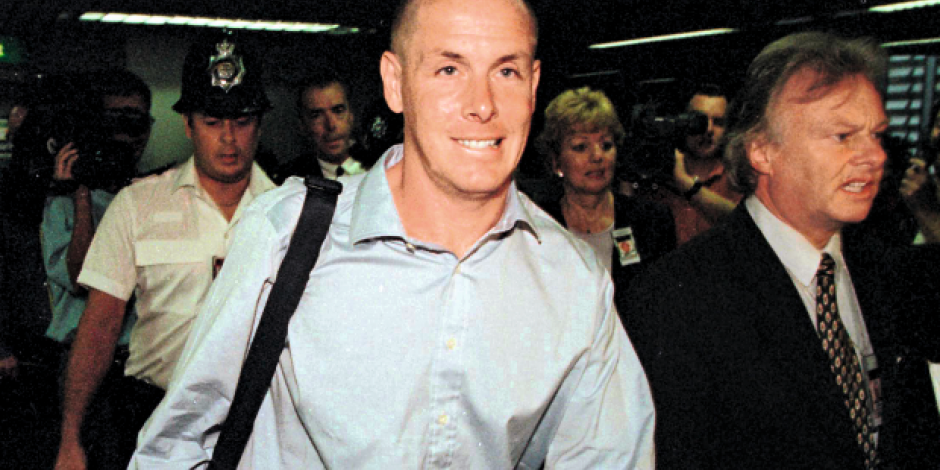

It wasn’t true, of course, and the discovery of BFS’s multimillion dollar losses was fast becoming inevitable. In late February 1995, just after celebrating his 28th birthday, Leeson and his wife, Lisa, fled South-East Asia. As the Barings board discussed a possible rescue package with the Bank of England, the extent of their losses was to revealenthüllen, aufdeckenrevealed to be a staggeringatemberaubendstaggering $1.3 billionMilliarde(n)billion. Barings collapsed, and its investors lost everything.

When Leeson arrived at Frankfurt Airport on 2 March, he was arrested. Despite the gravitySchweregravity of the chargeAnklagecharges facing him, the Serious Fraud Office did not apply to bring him back to the UK for trial. The establishment in London dismissed the crisis as having been caused by “one individual” rather than any systemic failure. Significantly, the markets to hold steadyhier: nicht einbrechenheld steady.

The extent of their losses was revealed to be a staggering $1.3 billion. Barings collapsed, and its investors lost everything.

Under headlines such as “Ego and Greed”, newspapers at the time described Leeson as a “fearsomeFurcht erregendfearsome trader”. But what exactly were his crimes? Despite the size of Barings’ losses, the Singapore arrest warrantHaftbefehlarrest warrant was limited to “forgeryFälschenforgery for the purpose of fraud”. Leeson faced 12 charges, including to amendanpassenamending prices and to implementdurchführenimplementing cross tradeKompensationsgeschäftcross trades. Eventually, having returned to Singapore, he was sentenced to six and a half years in prison. Subsequent investigations and reports to castigategeißelncastigated Barings executives for lack of oversight, improper management and lack of control. In July 1995, the Bank of England report stated that “the true position was not noticed earlier by reason of serious failure of controls and managerial confusion within Barings”. One senior Bank of England official with direct responsibility for Barings to resignzurücktretenresigned. Nobody else was ever charged.

In August 1998, not long after his marriage ended in divorce, Leeson to contract sth.an etw. erkrankencontracted colon cancerDickdarmkrebscolon cancer. He underwent emergency surgeryNotoperationemergency surgery and was released early from prison in July 1999. After lengthylangwieriglengthy treatment, Leeson slowly rebuilt his life, remarried and today lives in Ireland. He runs a consultancy practiceBeratungsbüroconsultancy practice and is engaged as an after-dinner speakerTischredner(in)after-dinner speaker. As he explains in Rogue Trader, the memories of Barings are never far away: “Every time there is a rogue-trader scandal it feels as though I am once more on the run again myself...”

In print and on screen

While fighting extradition to Singapore, Nick Leeson was held in Hoechst Prison, Frankfurt. There, he wrote a book about his experiences, which was published in 1996 as Rogue Trader – How I Brought Down Barings Bank and Shook the Financial World. Described by the Financial Times as “simultaneously entertaining and appalling”, the bestseller sets out Leeson’s background, ambitions and roller-coaster career at Barings. A dramatic story of risk, reward and disaster, it was adapted for the big screen in 1999 as Rogue Trader, directed by James Dearden, with Leeson played by Ewan McGregor.

Interview

Julian Earwaker spoke to Dan Davies, economist and author of Lying for Money: How Legendary Frauds Reveal the Workings of Our World, a book about Nick Leeson and the culture of fraud.

Julian Earwaker: Why is it that we are so susceptibleanfälligsusceptible to fraud in our society?

Dan Davies: Well, I mean it’s a hightrust economy. You can’t check up on everything, and for the things that are outside your direct ability to verify, you can either invest in checking mechanisms — which can be investing a lot in audit capabilitiesPrüfkompetenzenaudit capabilities or in technology — or it can be simply mean closing your business network to a small network of friends and relatives you trust. Or you can decide to deal with the problem by ignoring it and trusting the people you are doing business with. What we find out is that the solution of trust is vastlyerheblichvastly more efficient than the solution of checking up on everything. The thing about trusting people is that, by definition, you are vulnerableverletzlich, anfälligvulnerable to fraud.

Earwaker: The common factor of the frauds you reveal in Lying for Money is that the fraudsters do get caught. Is that the ultimate lesson?

Davies: They always get caught in the end, or the fraud always to fall apartauseinanderfallenfalls apart in the end, because a fraud, by nature, will generally have exponential growth built into it.

You know, once you’ve started taking money out of the accounts and adding to a sort of loss-making position, you’ve driven a wedgeKeilwedge between the real books and the books that you are reporting to head office. Therefore, the growth in what you have to do includes the growth on the legitimate business you are reporting plus the growth of the wedge.

Frauds always tend to snowball, therefore, and as with any exponential growth process, there comes a point where it can no longer be supported by the thing that is supporting it. So then it falls apart and collapses.

Earwaker: Nick Leeson doesn’t come out of your book too favourablypositivfavourably. Do you not rate him for his fraudster ability?

Davies: Well, a lot of that was the effect of reading lots of books about Leeson in a short space of time, because if you read multiple books about him and Barings, you suddenly realize that his autobiography is incredibly self-servingeigennützigself-serving and really selective.

He was someone of genuineechtgenuine talent, which is how he managed to get to put sb, in chargejmdm. die Verantwortung übertragenput in charge of Barings futuresTermin-Futures Singapore in the first place; but the fraud he carried out was kind of sitcom stuff. And then he was financing it by having a somewhat better understanding of the funding arrangements of Barings Bank than the board and senior management did. That wasn’t difficult, because the board and senior management of Barings Bank, like any large bank board, tend to be more concerned with strategy and with things that make money than with the plumbingKlempnerarbeitenplumbing and the funding and the kind of nuts and boltsMuttern und Schrauben; hier: Grundlagennuts and bolts of how the cash gets from one place to another.

Leeson wasn’t bad. He just wouldn’t admit the mistake. But the trouble is that you can psychologically profile guys like Leeson and Jérôme Kerviel at Société Générale and Kweku Adoboli at UBS. They all have the same kind of psychological characteristics. They tend to be outsiders. They tend not to come from the very best schools. They usually feel as if they have something to prove. They’re exceptionally hard workers, but they don’t admit mistakes. The trouble is that those are the psychological profiles of the most successful traders, too.

Lessons learned?

Rogue traders are typically loners who conduct high-risk deals, undetected, usually causing large losses for their clients and employers. Barings was described as a “wake up call that no one would forget”. But since 1995, more rogue traders have emerged, causing ever greater losses.

Top five rogue traders:

2012 Bruno Iksil, JPMorgan Chase, $9 billion

2008 Howie Hubler, Morgan Stanley, $9 billion

2008 Jérôme Kerviel, Société Générale, $7.2 billion

2006 Brian Hunter, Amaranth Advisors, $6.5 billion

1998 John Meriwether, Long-Term Capital Management, $4.6 billion

Neugierig auf mehr?

Dann nutzen Sie die Möglichkeit und stellen Sie sich Ihr optimales Abo ganz nach Ihren Wünschen zusammen.