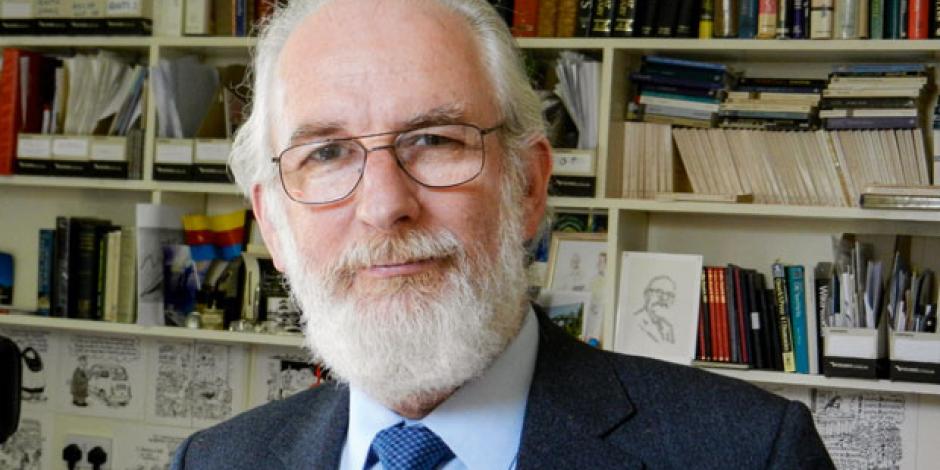

Interview: Julian Earwaker

Professor David Crystal is a linguist, lecturerDozent(in), Lektor(in)lecturer, editor and author of more than 100 books. He talks to Spotlight about the state of the English language today, the pace of change and English as a global and cultural language.

Spotlight: If you were a doctor giving the English language a health check today, what would be your prognosis?

Prof. David Crystal: Very healthy, and going from strength to strength. Of course, it is really the speakers whose linguistic health we’re checking, and what I see when I observe them is continuing and increasing variation and change. The internet, for example, has hugely increased the expressive richness of English (and other languages, of course), with many new styles; and wherever I look, I see these being used and developed, showing a natural and widespread creativity. To take just one tiny example: Twitter introduced the hashtag as a classificatory device (#Hamlet), and within just a few years, users had semantically extended it (#amazing) and had begun to speak it in everyday conversation. Some people see linguistic change as deteriorationVerschlechterung, Verfalldeterioration. I don’t. Change is the sign of a healthy language.

Change is the sign of a healthy language

Spotlight: What are the most significant trends in the English language?

Crystal: The increasing diversity that has come from its spread as a global language. This is unprecedentedbeispiellos, noch nie dagewesenunprecedented. No language has ever been spoken so widely. And what is especially interesting is to see the way different countries are working out how to balance the competing forces that govern this spread. On the one hand, there is the need for intelligibilityVerständlichkeitintelligibility — people need to understand each other on an international level. On the other hand, there is the need for identity — people want to express themselves in a local way. Of the two, the former has been the focus of study for a long time, through the notion of Standard English. Now the latter is beginning to be more systematically investigated, especially in the way a localeSchauplatzlocale adapts the language to express its culture.

Spotlight: Is the English language changing faster than in the past?

Crystal: Change doesn’t operate at a steady rate. It has peaks and troughsHöhen und Tiefenpeaks and troughs, and different aspects of language illustrate these in different periods. Vocabulary, for instance, peaked in the early Middle Ages (after the French takeover of England), then again in the Renaissance (with many Latin and Greek words arriving), and again in the Industrial Revolution (with a huge increase in scientific and technological terminology). Today, the digital revolution is speeding up the rate of change and may well lead to another peak, the ultimatemaximalultimate height of which we have yet to discover. I don’t sense a change of pace in most other aspects: grammar is to trundle alongentlangzuckelntrundling along with small changes, as it has done for several hundred years, and so are pronunciation and spelling. Punctuation is the other area that has been more noticeably to affectbeeinflussenaffected, with new styles very evident online.

Spotlight: What are the challenges for teaching English today and in the future?

Crystal: The main challenge is one that Spotlight is very good at meeting: introducing learners not just to the language, but also to the culture that lies behind it. Very few materials are available to help teachers systematically explore culture-specific language with their students, the kind of comprehension difficulty that arises when a British speaker says, “It was like Clapham Junction in there”, and the outsider has no idea what that means (“chaotic”, because that railway station is so complex). The Longman Dictionary of English Language and Culture was one such aid, but that is no longer being updated. I can see why. The task is enormous, when we consider the adaptations that have taken place in every country where English has established a presence — in other words, all countries nowadays.

The view that conversational English has less grammar than formal written English is a myth. The grammar is just different

Spotlight: Is there a risk that everyday English is becoming “grammar-light”?

Crystal: Not at all. The view that conversational English has less grammar than formal written English is a myth. The grammar is just different. The rules governing informal spoken constructions are just as many and “heavy” as those governing other styles. Learning how to use such comment clauses as “you know” or “you see” involves some quite tricky grammatical points. One mustn’t be to misleadin die Irre führenmisled by the way some written varieties of the language motivate the use of short sentences, as in Twitter or instant messaging. Those varieties do lead to a simpler kind of grammar, but not all internet styles are like that. Blogging, for example, displays quite complex grammar at times. And even when tweets are 140 characters long, they allow sentences of up to 30 or so words.

To predict the future of a language is to predict the future of society

Spotlight: Will global English continue to be dominant?

Crystal: Statistics indicate that it will for the foreseeablevorhersehbarforeseeable future. In the third edition of the Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, I recalculated the number of English users for all countries, using the same criteria as in earlier editions. Results have to be taken with the proverbialsprichwörtlichproverbial with a pinch of saltmit Vorsichtpinch of salt, of course, but the overall trend is very clear. From a total of around 1.5 billion in 1995, it grew to around 2 billion in 2003, and in 2018 had reached 2.3 billion. So, the growth continues, but it has begun to to flatten outflach werdenflatten out a bit. Even so, no other language is yet showing signs of comparablevergleichbarcomparable dominance, although in the unforeseeable future anything can happen, of course. To predict the future of a language is to predict the future of society.

Spotlight: Looking into your “Crystal” ball, what will the English language be like in 100 years’ time?

Crystal: The ball is cloudy. It’s never possible to predict language change. To take just two examples: who would have predicted in 2010, for example, that within a decade there would be a new suffix being creatively used in English: -exit? I hear all kinds of variations today — Mexit, Bexit, Sexit and so on, each with a clever meaning of some kind. Who would have predicted the kind of political oratoryRedekunstoratory we now associate with Donald Trump? Believe me, folksLeutefolks, we’re gonna make Spotlight great again!

Spotlight: What is the most important thing that all of your English studies and learning have taught you?

Crystal: To respect all languages and all varieties of language.

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (3rd edition), edited by David Crystal, is published by Cambridge University Press (ISBN 13: 978-1108437738). A Life Made of Words: the Poetry and Thought of John Bradburne by David Crystal is available from www.davidcrystal.com